DR. JACQUES-OLIVIER PESME WON’T CHANGE HIS ROUTINE to mark Earth Day.

The director of the UBC Wine Research Centre will likely enjoy his favorite vintage and think about the vines from which the grapes were grown. He follows that routine many days of the year, not just every April 22.

“Every day is Earth Day for us at the Wine Research Centre,” he says. “We’re always considering how we can better ensure a future for BC wines, especially in light of climate change.”

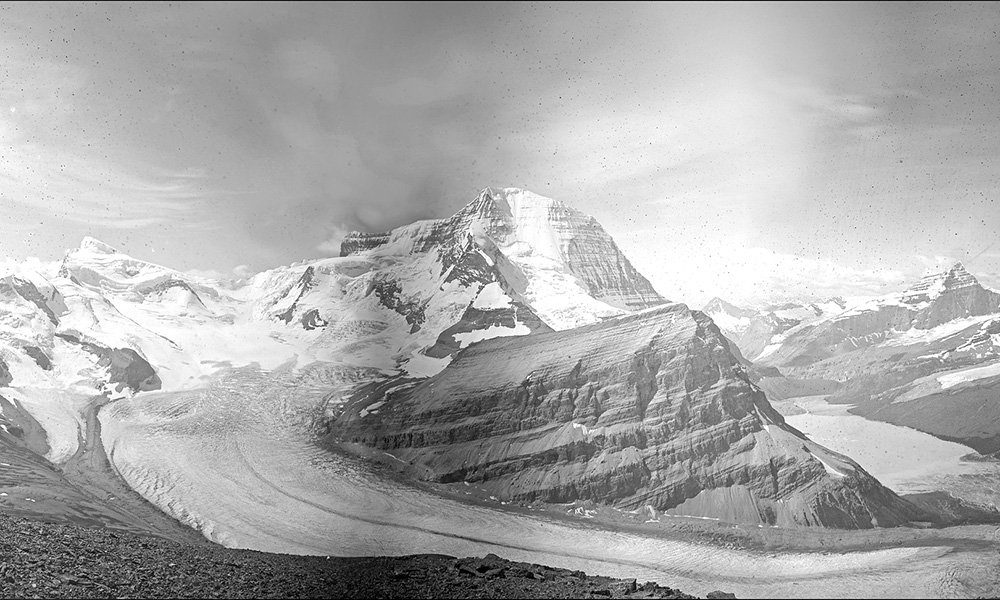

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the combined land and ocean temperature has increased at an average rate of 0.08 degrees Celsius per decade since 1880, but the average rate of increase since 1981 has been more than twice as fast, at 0.18 C per decade. In addition to rising temperatures, climate change has led to more severe storms across the globe, increased drought in already water-strapped regions and a warming, rising ocean.

It affects all aspects of our day-to-day lives, including transportation, energy production, the cost of living, and beyond. It’s not a problem for the future. Industries across the globe are absorbing real climate effects on their businesses now.

“The wine industry does not escape the rule. It’s also affected by the climate change challenge,” Dr. Pesme says. “Numerous factors affect the taste of wine, including growing climate, hours of sunlight, water levels, warmth and nutrients. It’s well-known that that climate has direct impact on the flavor of ripe grapes, positive in most cases, but dramatic when the climate is changing radically. Science shows that BC will be more regularly affected by intense climate episodes, extreme heat or early frost, for instance.”

To that end, the Centre is engaged in supporting the development of a competitive and sustainable BC wine industry through world-class research, excellence in wine education, practical solutions and knowledge mobilization.

“We have some of our team working on the effect of climate change on vineyards in BC, but also elsewhere in the world. They’re precisely measuring the evolution of our climate,” Dr. Pesme says. “We have other teams and researchers working on the effects of a climate hazard provoked by climate change. Take, for example, a wine region affected by wildfires. What effect will the smoke have on the grapes and then the taste of its wines?”

Precise data at the micro level is vital in the search for climate solutions.

The Centre leans into three pillars for its research: grapes, vineyards and soils; wine and fermentation, winery performance and sustainability; and, wine territory competitiveness. Study happens in the field (or the vineyards, in this case) and at three locations in Vancouver and Kelowna. The Centre’s Mass Spectrometry Core Facility can analyze fragrance and aroma compounds, flavonoids and anthocyanins (pigment) in fruit, as well as metabolite profiling of small molecules.

UBC also established a Wine Library in Vancouver with donations from dozens of BC wineries. The library collection was established in order to study which grape varietals do best in specific micro climates in BC, and to study the long-term aging abilities of those wines.

Finally, the Plant Growth Facility at UBC Okanagan is a state-of-the-art greenhouse that opened in September 2020. The 5,000-square-foot facility has computer-controlled light and temperature programs for large projects, and allows for isolation of different growth and treatment protocols.

“As the climate situation evolves, we need to nurture the knowledge of owners and staff at vineyards. A precise knowledge of what we call micro-climate situations, as well as soil studies, will help us better understand how climate change affects a particular wine territory,” Dr. Pesme says.

He says more detailed weather stations in the Okanagan and Vancouver Island where climate conditions may vary a lot within few hundred meters is an important next step. “There are already existing weather stations in BC; however, the information is not coordinated and shared by all the parties. This is an absolute need to grow grapes wisely, especially in the context of climate change.”

New innovations are emerging in response to the climate change challenge, and low-impact and knowledge-based wine making techniques that are studied at UBC and UBC Okanagan are being harnessed globally as part of the effort to mitigate impacts of a more extreme climate.

“Here in BC, around Okanagan Lake, there are approximately 80 varieties of vine. Climate change may spur winemakers to change grapes they grow, according to the evolution of the climate and the best combination of climate, type of soil and the Okanagan condition.”

Dr. Pesme uses the United Kingdom as an example of a region that has benefited recently from climate change with the emergence of a growing wine industry—sparkling wines in particular. The UK has always been an important and influential market for wines, predominantly imported. Nowadays, thanks to the climate’s evolution, there is a strong argument to support the development of a domestic wine sector, inspired by the Champagne region of France.

“The UBC Wine Research Centre wants to power vintners and grape growers with more and specific information to address climate change,” Dr. Pesme says, “because this is not just about wine. The world needs real solutions to extreme climate. We need better methods and knowledge in agriculture and production. The Wine Research Centre wants to contribute to those solutions.

“Our collective future depends on it.”

The post Red or white & green: How wine making fits into Earth Day appeared first on UBC Okanagan News.